In 2024, Latin America and the Caribbean experienced a record-breaking dengue outbreak, with unprecedented infection rates linked to the mosquito vector Aedes aegypti.

As dengue cases surge globally, especially in Latin America and Southeast Asia, three major biological control strategies have emerged as key tools in combating the spread of dengue: Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes, genetically modified mosquitoes, and natural predators targeting Aedes aegypti (A. aegypti).

Previously, I explored how artificial intelligence (AI) is enhancing these mosquito control strategies across Latin American regions.

In this post, I take a closer look at how Wolbachia bacteria—a naturally occurring endosymbiont—is leading an innovative and eco-friendly approach to dengue vector control through the infection and population management of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes.

But what is Wolbachia?

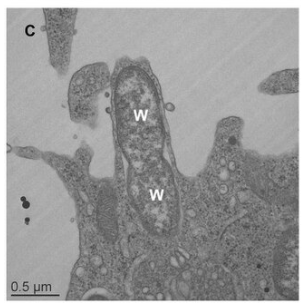

Figure 1. Wolbachia bacteria (W) replicating inside fixed cells isolated from the Aedes albopictus mosquito. Image taken from a type of microscopy named transmission electron microscopy. Modified picture from Vincent et al. PLoS One. 2015.

Wolbachia is a genus of bacteria that naturally infects many arthropods. In fact, the word arthropod comes from the Latin Arthropoda, meaning “jointed foot.” Just like humans, mosquitoes face their own microbial threats and Wolbachia is one of the most fascinating.

Wolbachia is not harmful to humans. Instead, it acts as a symbiont, an organism that lives in a long-term relationship with another, usually larger, host.

Wolbachia can block viral disease transmission by blocking the transmission of the virus or decreasing the life span of the mosquito vector.

This makes Wolbachia a powerful tool in controlling the spread of viral diseases carried by mosquitoes, especially the Aedes aegypti mosquito, which is the primary vector for dengue.

Here’s the twist: Wolbachia does not naturally infect Aedes aegypti, the primary carrier of the dengue virus. So…

Can Wolbachia Stop Dengue-Carrying Aedes aegypti?

Scientists have developed specialized strains of Wolbachia, including wMel and wMelPop-CLA, that can infect A. aegypti and disrupt their ability to transmit viruses such as dengue, Zika, and chikungunya.

Figure 2. Drosophila melanogaster flies bred in the laboratory. Source: Flickr.

In a pivotal 2011 study published in Nature by Hoffmann et al., researchers successfully introduced the wMel strain of Wolbachia, originally found in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster, into Aedes aegypti mosquitoes.

They released wMel-infected mosquitoes in two locations in Northern Australia and monitored the spread of infection using ovitraps and genetic testing over several months.

Key Outcomes of the Study:

- Rapid Spread: The Wolbachia infection spread rapidly and reached near-complete saturation within just a few months.

- Minimal Fitness Cost: Infected mosquitoes experienced low biological fitness costs, making it easier for them to thrive and spread the bacterium.

- Potential for Disease Suppression: The success of the wMel strain indicated that Wolbachia-based mosquito control could be a powerful tool in reducing dengue transmission and combating other mosquito-borne viruses.

Figure 3. Example of an ovitrap, a trap designed to collect mosquito eggs. Source: Flickr

Another influential study, published by Walker et al. in Nature (2011), demonstrated that both wMel and wMelPop-CLA strains of Wolbachia could:

- Rapidly invade Aedes aegypti populations

- Maintain high maternal transmission rates

- Block the transmission of dengue virus serotype 2 (DENV-2)

Overall, Wolbachia works by blocking pathogens (such as dengue, Zika, and Chikungunya), reducing offspring while favoring Wolbachia-infected females, inducing cytoplasmic incompatibility, and reducing the mosquito’s lifespan.

Many field trials have shown significant reduction of dengue incidence, up to 96% in Australia and 77% in Indonesia.

The World Mosquito Program leads efforts to use Wolbachia to fight dengue worldwide.

What is the impact of Wolbachia mosquito release in Latin America?

Wolbachia is one of the most endosymbiotic bacteria in nature, found largely in invertebrates (60-70% of insects, some spiders and mites, etc.) worldwide.

We know that insects represent a significant portion of animal species in Latin America. In areas like the Amazon rainforest in Brazil, insects make up over 90% of animal species.

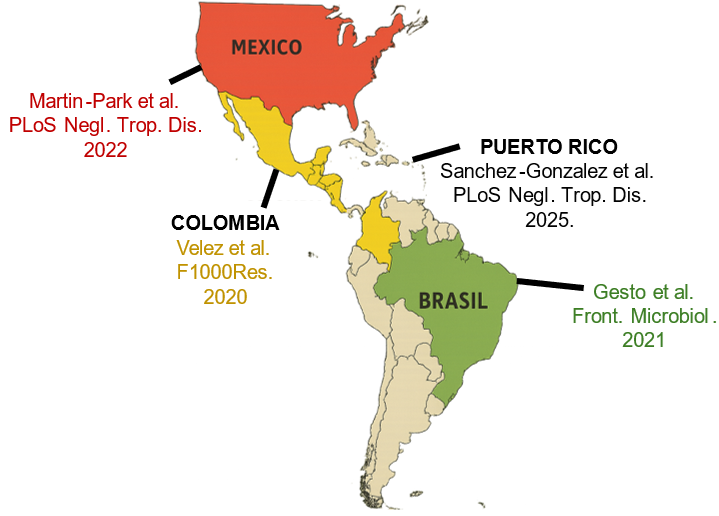

The deployment of Wolbachia-infected Aedes aegypti mosquitoes has shown tremendous promise in reducing dengue transmission throughout Latin America. Below are key examples of Wolbachia mosquito release programs and their outcomes across the region:

Figure 5. Published field releases of Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes in Latin America.

Field release in Mexico

Martin-Park et al., PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2022

In a pioneering effort to reduce dengue-spreading mosquito populations, researchers in Mexico released sterile male Aedes aegypti mosquitoes using a hybrid approach combining the Incompatible Insect Technique (IIT) and the Sterile Insect Technique (SIT). These males, sterilized through a combination of Wolbachia infection and radiation, led to dramatic reductions in mosquito populations in treated zones.

Large-scale deployment in Brazil

Gesto et al., Front. Microbiol. 2021

In Rio de Janeiro, scientists launched a large-scale Wolbachia mosquito release program targeting the Aedes aegypti population. The study demonstrated a successful establishment and long-term presence of the Wolbachia bacteria in local mosquitoes, showcasing its value as part of an integrated vector management strategy for dengue control in Brazil.

Major dengue reduction in Colombia

Velez et al., F1000Res. 2020

In a large-scale dengue intervention program, Colombian neighborhoods where Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes were established saw dengue cases drop by 94% to 97%. This striking result reinforces the effectiveness of Wolbachia-based vector control as a sustainable public health solution.

Recent Wolbachia release in Puerto Rico

Sanchez-Gonzalez et al., PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2025

A field trial conducted in Puerto Rico tested an innovative mosquito control method by releasing incompatible Aedes aegypti males infected with Wolbachia bacteria into targeted urban areas. These non-biting males were strategically deployed to reduce mosquito reproduction, and researchers monitored population dynamics over time using standardized trapping methods. The results showed a substantial decrease in local Aedes aegypti populations, highlighting the effectiveness of Wolbachia-based mosquito suppression. This environmentally friendly approach offers a promising vector control strategy to combat mosquito-borne diseases like dengue fever, Zika virus, and chikungunya. The study reinforces the value of biological control methods in integrated mosquito management programs.

Is Wolbachia safe to humans?

While Wolbachia bacteria are well-known for infecting insects, including mosquitoes, it is important to understand their safety profile, especially in regions like Latin America, where insects are also a traditional part of the diet.

Figure 4. A basket of Chapulines (roasted crickets) in Tepoztlán, Mexico. Source: Meutia Chaerani, Wikimedia Commons.

Countries such as Mexico, Brazil, Ecuador, and Colombia have a long history of entomophagy, which is the practice of eating insects. In fact, Mexico leads in both cultural acceptance and diversity of edible insects.

Species like ants and crickets can contain between 9–77% protein by dry weight, significantly more than beef, which typically ranges from 25–28%. Since Wolbachia is naturally present in over 60% of insect species, humans are regularly exposed to it through environmental contact and even consumption.

Despite its powerful effects on mosquito reproduction and virus transmission, Wolbachia poses no threat to humans or animals. It does not infect mammals, and there are no reports of it causing disease in humans.

A study by Popovici et al. demonstrated that Wolbachia-infected Aedes aegypti mosquito bites did not trigger any immune response in human volunteers, further supporting Wolbachia’s safety profile.

Unlike mosquito-borne viruses such as dengue, Zika, or chikungunya, Wolbachia cannot be transmitted to humans through bites. Additionally, it cannot survive or replicate outside its insect host, making it biologically safe for use in mosquito control programs

Are there any risks or drawbacks to using Wolbachia for mosquito control?

While Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes are a groundbreaking tool in the fight against dengue and other mosquito-borne diseases, some researchers caution that there may be unintended ecological consequences if deployment is not carefully managed.

Figure 5. Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes could be easily killed. Source: Flickr

In a 2023 Lancet commentary, Pavan et al. raised concerns about Brazil’s ambitious plan to build the world’s largest mosquito biofactory, aimed at releasing five billion Wolbachia-infected Aedes aegypti mosquitoes annually, beginning in 2024.

Their main concerns include:

Genetic mismatch and insecticide resistance

One major issue is genetic mismatch. Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes released in Brazil may not be well-adapted to local environments. For instance, if they lack resistance to widely used insecticides such as pyrethroids, they may quickly be eliminated. In an earlier trial in Brazil, infection rates dropped from 65% to 10%, primarily due to incompatibility between released and local mosquito populations

Risk of mosquito population homogenization

Mass-releasing a genetically uniform mosquito strain across diverse ecological zones could lead to population homogenization. This loss of genetic diversity might unintentionally enhance negative traits, such as:

- Increased virus transmission potential

- Reduced sensitivity to repellents and insecticides

- More aggressive biting behavior

The need for responsible implementation

While Wolbachia-based vector control remains a powerful and eco-friendly alternative to chemical insecticides, its long-term success depends on ecological and genetic compatibility. Regional variations in mosquito genetics and environmental conditions must be considered to avoid counterproductive outcomes.

Strategically tailoring mosquito release programs to local settings ensures that Wolbachia deployments are not only effective but also sustainable.