Source: Charliebrown7034~commonswiki | Wikimedia Commons

Climate change is not the only environmental factor reshaping public health in Latin America. Artificial light at night (ALAN), a growing form of light pollution, is increasingly disrupting natural ecosystems. Importantly, it is now being linked to higher rates of mosquito-borne diseases such as dengue, Zika, chikungunya, and yellow fever.

Climate change is not the only environmental factor reshaping public health in Latin America. Artificial light at night (ALAN), a growing form of light pollution, is increasingly disrupting natural ecosystems. Importantly, it is now being linked to higher rates of mosquito-borne diseases such as dengue, Zika, chikungunya, and yellow fever.

While light pollution is often associated with developed countries, Latin American nations like Brazil, Mexico, Chile, and Argentina are experiencing rapid urban growth that brings with it heightened levels of ALAN.

This artificial illumination not only impacts the visibility of stars or disrupt wildlife. It also plays a direct role in shaping mosquito behavior, ultimately affecting human health.

In this blog, we take a closer look at the recent study by Rund et al. published in the American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. It reveals that exposure to ALAN significantly alters the biting behavior of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes.

Table of Contents

Study Design and Methods

Source: The U.S. National Archives | Picryl

Researchers examined how ALAN influences the biting behavior of Aedes aegypti, the primary mosquito species responsible for spreading diseases like dengue, Zika, chikungunya, and yellow fever.

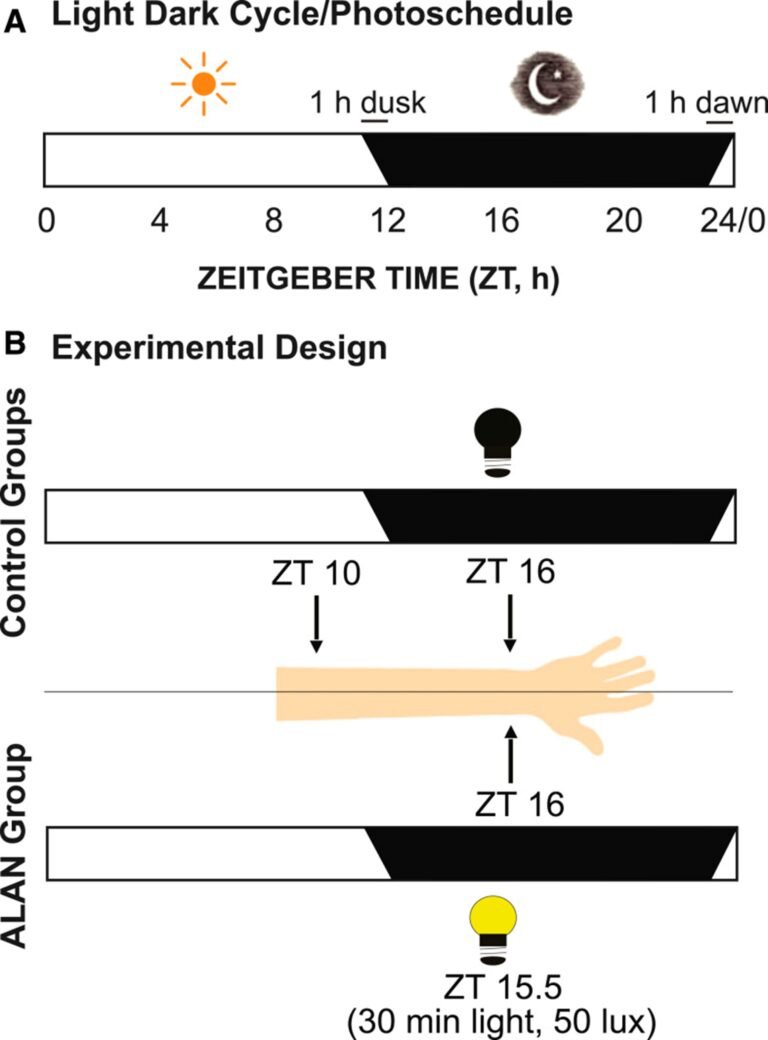

Female Aedes aegypti mosquitoes were raised in stable conditions with regulated temperature and humidity, following a 12-hour day and 12-hour night cycle known as Zeitgeber Time (ZT). ZT is a standardized reference used to measure circadian rhythms.

To measure the effect of ALAN on their feeding habits, scientists allowed groups of 30 mosquitoes to feed on a human arm for six minutes and recorded how many took a blood meal.

The experiment included three groups:

- ZT10 Group: Mosquitoes feeding during their natural late-afternoon active period.

- ZT16 Group: Mosquitoes feeding at midnight, a time when they are typically inactive.

- ALAN Group: Mosquitoes briefly exposed to dim white light during the night before feeding, simulating light pollution.

The feeding experiment was repeated five times using automated light controls to prevent disturbance. Researchers then analyzed the data using one-way ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey tests to determine whether the differences in biting behavior between the groups were statistically significant.

Source: Figure 1 from Rund et al. published in the American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene | Open Access.

Artificial Light Exposure Doubles Rate of Mosquito Bites at Night

The study revealed a dramatic shift in Aedes aegypti mosquito behavior due to ALAN exposure. Under normal conditions, 82% of mosquitoes in the daytime control group (ZT10) fed on a human arm, while only 29% did so in the nighttime control group (ZT16), confirming naturally low nighttime activity.

In the ALAN-exposed group, 59% of mosquitoes fed, doubling the natural nighttime biting rate. Even brief artificial light exposure can disrupt feeding patterns and increase the nighttime transmission risk of arboviruses.

The study warns that even brief ALAN exposure can double nighttime biting by Aedes aegypti. This surge isn’t driven by circadian changes but by a direct behavioral response, pushing typically daytime mosquitoes to bite after dark.

What This Means for Latin America

ALAN is spreading rapidly across Latin America, posing a serious yet often overlooked threat to public health. According to the World Atlas of Artificial Night Sky Brightness, over 80% of the global population, including a significant portion of urban Latin Americans, now lives under light-polluted skies.

In Argentina, almost 58% of the population experiences extremely bright night skies, while in Brazil, artificial light impacts 35% of native vegetation and 25% of current landscapes, revealing its reach into both natural and urban environments. Along the South American coastline, approximately 15.5% of the area is exposed to ALAN, particularly in densely populated coastal cities.

As cities throughout Latin America continue to expand and brighten, light pollution may quietly fuel the spread of arboviral diseases by extending the hours mosquitoes are active and biting. This effect could undermine current prevention strategies focused on daytime exposure and lead to increased infection rates, particularly in communities with limited mosquito protection at night.

Call to Action

Source: Alun Zuk | Wikimedia Commons

Latin America has reason to be especially concerned about the rise in Aedes aegypti biting behavior under ALAN. The region already suffers a heavy burden from mosquito-borne viruses that thrive in densely populated, urban areas.

To protect our communities from mosquito-borne diseases, we must look beyond mosquito control and recognize how our modern lifestyles contribute to the problem.

The glow of streetlights, billboards, and even home lighting can unintentionally fuel mosquito activity. As cities across Latin America continue to grow brighter, it’s time to rethink how we light our environments.

Support urban policies that reduce light pollution, use motion-sensing or shielded outdoor lights, and help spread awareness about how artificial light affects mosquito behavior. Small changes in how we illuminate our homes and neighborhoods can make a big difference in protecting public health, and the planet.