Figure 1. People in garbage landfill in Mexico.

Source: Curt Carnemark/ Wolrd Bank via Flickr.

Sometimes, love is hard to find, but certain bacteria, like Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori), are not. In fact, Latin America and the Caribbean are among the regions with the highest rates of H. pylori infection in the world.

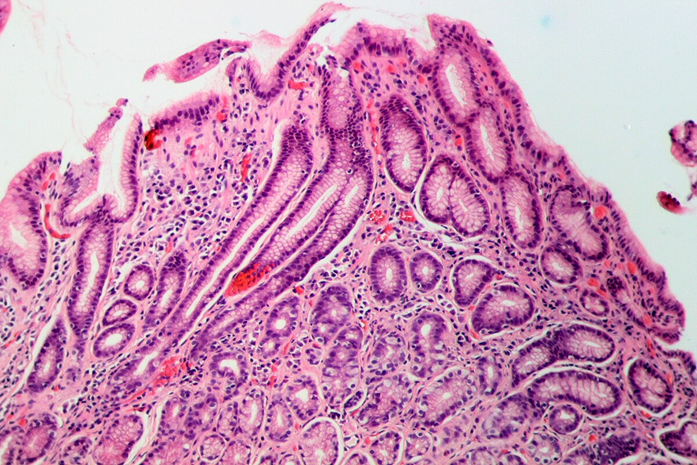

First identified as Campylobacter pylori and renamed H. pylori in 1989, this microbe is the leading cause of gastritis. It is also responsible for peptic ulcers (in 10–15% of infected individuals), gastric cancer (around 1%), and gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma.

In 2012, H. pylori was linked to over one-third (35.4%) of all cancer cases caused by infectious agents. Even more alarming, it was associated with 89% of non-cardia gastric adenocarcinoma cases. In the U.S., Hispanic and Native American/Alaska Native (NA/AN) patients show the highest prevalence of H. pylori-related upper gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms and diagnoses.

In a previous blog, I discussed how Latino cultural factors contribute to the disproportionately high rates of H. pylori infection and the elevated risk of gastric cancer among asymptomatic Hispanic populations.

Here, I dive deeper into the history, transmission, and biological traits of this pathogen, using insights from the recent Nature Reviews Disease Primers article by Malfertheiner et al.

Table of Contents

Discovery of Helicobacter pylori’s Involvement in Chronic Gastritis

Figure 2. Nobel Prize plinth and medal replica unveiling. Source: Queen’s University via Flickr.

It was not until 1982 that Professors J. Robin Warren and Barry J. Marshall identified H. pylori as the cause of chronic gastritis, earning them the 2005 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

Before their discovery, stomach ulcers were believed to result from stress or excess acid, not bacterial infection. Koch’s postulates, developed in the 19th century, laid the foundation for this breakthrough, even if modern microbiology has revealed exceptions (e.g., prion diseases).

Today, we know that H. pylori infects half of the world’s population. Around 80% of cases remain symptom-free, yet silently progress to conditions like gastritis or ulcers. Even more concerning is the rise of antibiotic-resistant H. pylori strains, particularly in developing nations.

Increased Transmission and Persistence of H. pylori in Latin America

H. pylori infection is linked to age, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, hygiene, and geographic location. Once contracted, it often persists for life. The bacterium spreads via contact with infected stool, vomit, saliva, or contaminated food and water.

In low-resource settings like parts of Latin America, transmission within families, especially from mothers to children, is common. The widespread cultural practice of food-sharing in Hispanic communities may further increase exposure risk.

While the global prevalence of H. pylori is decreasing due to better sanitation, Latin America has not seen the same decline. Studies show infection rates remain high, often exceeding 50%, with rising antibiotic resistance.

Numerous scientific studies have consistently shown that individuals of Hispanic or Latino heritage are at a higher risk for H. pylori infection. This increased prevalence is a growing concern, especially due to the associated risk of gastric diseases, including stomach cancer.

A study by Parma et al. analyzed blood samples from 284 men in Texas and found that Hispanic men had significantly higher rates of H. pylori infection and gastric cancer compared to non-Hispanic white men. The study also identified obesity as a contributing factor to this elevated risk.

Recent research by Tsang et al. (2022) further underscores that H. pylori remains a major public health threat in developing countries, particularly in Latin America. Their findings show that H. pylori seroprevalence is not only persistently high but also varies significantly across different Hispanic and Latino backgrounds.

Figure 3. District celebrates Hispanic Heritage month. Source: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Europe District via Flickr.

Earlier data from a 2014 study by Patel et al. revealed a similar trend: H. pylori infection rates were highest among Hispanics (40.9%), followed by Black populations (29.1%) and whites (7.9%).

Supporting this pattern, a recent publication in The Lancet Regional Health by Torres-Roman et al. highlighted that H. pylori prevalence in Hispanic and Latino populations across the United States, Latin America, and the Caribbean often exceeds 50%. Alarmingly, the rise in antibiotic-resistant H. pylori strains further complicates treatment and control efforts.

Conclusion: A Hidden Epidemic in Hispanic and Latin American Communities

H. pylori may be invisible to the naked eye, but its impact on public health, especially in Hispanic and Latin American populations, is anything but small. Decades after its discovery revolutionized our understanding of gastritis and gastric cancer, H. pylori continues to silently infect millions, particularly in regions burdened by poverty, limited access to healthcare, and persistent social inequalities.

The consistently high prevalence of H. pylori infection among Hispanic and Latino communities in both the United States and Latin America, often exceeding 50%, underscores the urgent need for culturally informed education, early screening programs, and improved access to effective treatments. Rising antibiotic resistance only adds urgency to this growing health threat.

Addressing H. pylori infection is not just a matter of treating a bacterium; it’s about confronting the systemic conditions that allow it to thrive. As we deepen our understanding of this pathogen’s biology, history, and impact, it becomes clear: tackling H. pylori requires not just science, but public health commitment, policy change, and community-driven solutions.