Pediatrician at work. Photo by Defense Visual Information Distribution Service via Picryl.

Highlights

- Dengue can occur without fever, and current guidelines miss it.

- Afebrile dengue is not always mild or harmless.

- Children are especially vulnerable to misdiagnosis.

- Fever-based surveillance creates a dangerous blind spot.

The World Health Organization’s dengue case definitions require fever for diagnosis.

Yet, the long-term pediatric cohort studied in the paper published by Carrillo et al. in The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health in Nicaragua found something striking: laboratory-confirmed dengue can occur without fever, and this pattern would be missed by standard surveillance.

Among the 1,405 laboratory-confirmed dengue cases in the study, 62 were afebrile, meaning children did not meet the traditional fever requirement used in most international case definitions.

What’s more, some of these afebrile cases still showed warning signs of disease severity, including symptoms associated with more serious progression.

These findings have major implications. When guidelines require fever for testing or reporting, afebrile dengue goes undetected.

This is especially problematic in pediatric populations where immune responses and symptom expression can differ from adults.

Because afebrile infants and children may look clinically similar to Zika or other viral illnesses, noisy surveillance systems may misclassify or ignore them.

High Risk of Misdiagnosing Afebrile Dengue

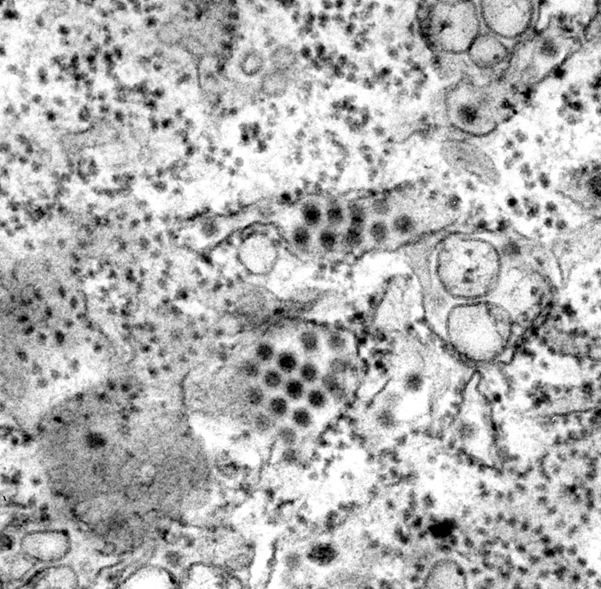

Dengue virus particles. Photo by Frederick Murphy and Cynthia Goldsmith USCDCP via Pixnio.

In the Nicaraguan cohort, fever was almost universal in chikungunya and very common in dengue, but Zika often presented without fever.

Without fever, these 62 dengue cases could easily have been labelled as Zika or another mild febrile illness. However, some carried warning signs that clinicians ordinarily monitor more closely.

This underscores an important lesson for pediatric care and public health. That is, diagnostic criteria need to reflect real clinical patterns, not just textbook definitions.

If afebrile dengue is more common than previously recognized, especially among children, case definitions must adapt to improve surveillance, triage, and management.

Why This Matters

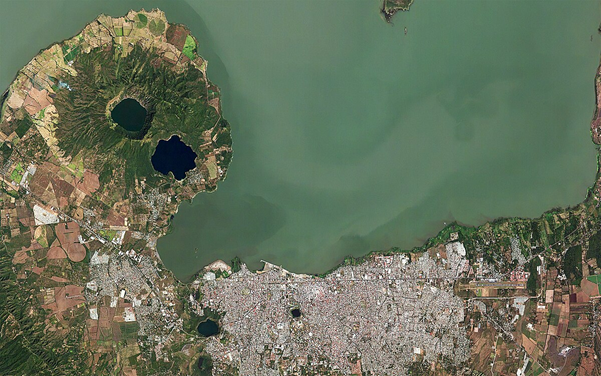

Managua, Nicaragua. Photo by Axelspace Corporation via Wikimedia Commons.

An 18-year pediatric cohort study from Nicaragua challenges one of the most entrenched assumptions in dengue surveillance: that fever is required for diagnosis.

In research published by Carrillo et al. in The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, investigators identified 62 laboratory-confirmed dengue cases in children who never developed fever, cases that would be excluded under current WHO case definitions.

Crucially, some afebrile children still showed warning signs associated with dengue severity, meaning they were not clinically benign.

In a setting where dengue, Zika, and chikungunya co-circulate, these children could easily be misclassified as Zika or dismissed as mild viral illness.

The study highlights a pediatric-specific blind spot: children may mount different immune responses than adults, producing real dengue disease without meeting textbook criteria.

Surveillance systems that rely on fever alone risk systematically undercounting cases and delaying care.

If surveillance requires fever, afebrile dengue becomes invisible.

Recognizing and integrating these cases into clinical guidance is essential to protect children and strengthen outbreak response.

Stay Informed

Photo by DigiGal DZiner via Wikimedia Commons.

Afebrile dengue is not rare, it is underrecognized. Meanwhile, missed cases shape outbreaks, surveillance data, and pediatric outcomes across endemic regions.

Pathogenos translates peer-reviewed infectious disease research into clear, evidence-based insights you can use in real clinical and public health settings.

Subscribe to Pathogenos for research-driven updates on dengue, Zika, chikungunya, and emerging pathogens, clear explanations of studies that challenge outdated guidelines, and actionable insights for clinicians, researchers, and public health professionals.