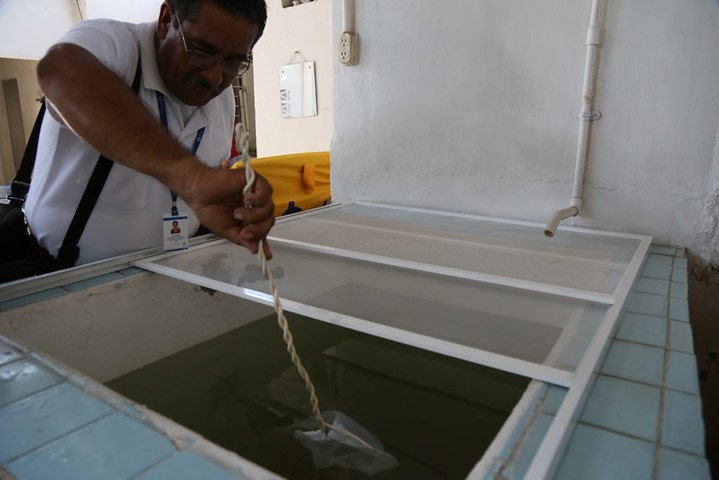

Source: PAHO’s photo stream, TDR COLOMBIA DENGUE 2013 2671.

On March 18, 2025, the CDC issued an urgent health advisory highlighting the growing dengue threat amidst funding cuts in mosquito-borne research, including those impacting dengue surveillance.

The agency reported that approximately 3,500 U.S. travelers contracted dengue abroad in 2025, and this number is expected to rise as outbreaks intensify worldwide. Latin America, Southeast Asia, and other tropical regions are facing unprecedented dengue surges, driving home the urgent need for stronger, more responsive dengue surveillance systems.

Political instability in the United States is threatening public health research and programs, especially those focused on mosquito-borne diseases like dengue. Yet, dengue virus remains indifferent to these budget debates.

Whether funding for mosquito-borne disease programs at the CDC is cut or preserved in the Fiscal Year 2026 budget, one fact remains: dengue continues to spread. Without proactive measures to control it, dengue will keep growing, much like an untended garden that quickly becomes overrun by weeds.

Even with advancements in diagnostic tools and mosquito control strategies, many dengue-endemic countries struggle with fragmented surveillance systems, limited laboratory capacity, and weak coordination between sectors.

These gaps make it difficult to detect outbreaks early and respond effectively, allowing the virus to spread unchecked.

In this blog post, I review three studies that highlight the ongoing challenges of dengue vector surveillance in Latin America, challenges that have global implications for controlling this growing public health threat.

A Severe Disconnect in Global Dengue Surveillance Efforts

Source: itolya420.getarchive.net (link)

Need: Despite progress in managing dengue, many countries where dengue is common still struggle with weak and fragmented surveillance systems. There is little standardization between how human cases are reported, how the virus is detected, how mosquito populations are monitored, and how environmental data is collected.

This lack of coordination, combined with limited lab capacity, outdated mosquito surveillance tools, and insufficient funding, makes it harder to detect outbreaks early, especially during periods of low transmission between epidemics (inter-epidemic periods).

Insights: In a 2011 article note published in the Western Pacific Surveillance and Response Journal, researcher Lee Ching reviewed factors contributing to the challenge in dengue surveillance.

The author discussed that while early mosquito control programs in the mid-20th century (such as eliminating mosquito breeding sites) temporarily reduced dengue, the virus made a strong comeback due to the failure to integrate new technologies into surveillance efforts.

Tools like advanced diagnostics, genomic sequencing, mapping, and data analytics show great promise but have not been widely adopted because of limited funding and weak health infrastructure.

Some regional and international partnerships, like the Asia Pacific Dengue Partnership, have shown potential. However, overall dengue surveillance systems remain underfunded, poorly integrated, and inconsistently applied across countries.

Bottom Line: The study concludes that long-term control of dengue will require steady investment in integrated surveillance platforms, consistent data reporting systems, strong mosquito control programs, and close cooperation between sectors and across national borders.

Dengue Reporting is Too Passive

Source: pix4free.org (link)

Need: Routine dengue surveillance in countries where the disease is common is essential to track how dengue spreads and to predict outbreaks. However, many current systems rely on passive surveillance, where cases are only reported when patients seek care. This approach often misses many infections, especially mild or asymptomatic ones, leading to underestimates of true dengue incidence and making it harder to forecast future outbreaks accurately.

Methods: In a 2016 study published in the International Journal of Infectious Diseases, Sarti et al. compared passive and active dengue surveillance methods.

Passive surveillance depended on reports from clinics and hospitals, while active surveillance involved going directly into communities: screening households, collecting blood samples, and testing for dengue infections.

This head-to-head comparison allowed researchers to evaluate how each system performed in detecting cases, how timely the data were, and how accurate the overall surveillance was.

Findings: Active surveillance identified far more cases than passive surveillance, often detecting several times more infections. Many of these were mild or symptom-free cases that would not have been captured otherwise.

Passive surveillance consistently underestimated the true number of dengue cases and was slower in detecting outbreaks. While active surveillance requires more resources, it provided much more accurate data and offered earlier warnings of rising dengue activity. This allowed health officials to act sooner and respond more effectively.

Implications: To improve dengue outbreak prediction and public health response, countries where dengue is endemic should combine passive reporting with targeted active surveillance, especially during high-risk periods. Adding active surveillance helps improve data accuracy

Many Diagnostic Blind Spots and Limited Funding for Dengue Surveillance

Source: pix4free.org ( link)

Need: The study by Tapia-Conyer et al., published in the Journal of Clinical Virology (2009), highlights that many countries where dengue is endemic face serious challenges in accurate dengue surveillance due to diagnostic limitations. Misdiagnosis is common because dengue symptoms overlap with many other febrile illnesses. In addition, a large proportion of dengue infections are mild or asymptomatic, making them harder to detect through routine clinical surveillance.

These problems are made worse by financial constraints, i.e., limited laboratory infrastructure and insufficient funding prevent national health systems from maintaining comprehensive surveillance programs. As a result, the true burden of dengue is often underestimated, delaying public health responses and increasing the risk of larger outbreaks.

Methods: This review analyzed evidence from multiple epidemiological and surveillance studies conducted in dengue-endemic regions. The authors examined diagnostic accuracy, the prevalence of asymptomatic infections, and the economic feasibility of different surveillance strategies.

They compared passive case detection (such as routine hospital reports) with more proactive methods like community-based active surveillance, vaccine programs, serological surveys, and molecular diagnostics (such as PCR testing). The goal was to evaluate how different approaches perform under resource-limited conditions.

Findings:

- High rates of undetected infections: Many dengue cases are asymptomatic or subclinical but still contribute to ongoing transmission. These missed cases distort official incidence rates and hide the full scale of dengue spread.

- Weak clinical reporting: Heavy reliance on routine clinical diagnoses leads to significant underreporting, especially where diagnostic laboratory testing is unavailable or limited. The non-specific nature of dengue symptoms further complicates accurate detection.

- Financial challenges: Many dengue-endemic countries lack the necessary funding to support adequate diagnostics, mosquito surveillance, or the staff needed for active case detection and serological testing.

- Strategic recommendations: The study recommends integrating serological and molecular diagnostics (such as PCR), improving vaccination strategies, expanding active surveillance programs, and improving financial investment. It also calls for standardized case definitions, better diagnostic guidelines, and international resource-sharing partnerships to help overcome disparities in infrastructure and capacity.

Bottom Line: Without addressing diagnostic gaps, especially in detecting mild or asymptomatic cases, and overcoming financial constraints, dengue surveillance will continue to underestimate the true incidence of the disease. This underreporting weakens outbreak preparedness and response efforts. Strengthening dengue surveillance requires greater investment in laboratory capacity, expanded active case detection, standardized protocols, and sustainable financial and institutional support.

In summary

Across these studies, a consistent message emerges: Without improved diagnostics, greater financial investment, active case detection, and standardized global protocols, dengue surveillance will continue to underestimate the true burden of the disease. Strengthening surveillance is essential to improve early outbreak detection, guide public health responses, and reduce the impact of dengue worldwide.