Highlights

- Dengue ranges from mild fever to life-threatening severe disease.

- Severe dengue is driven by plasma leakage, not bleeding alone.

- Greatest risk occurs when fever breaks, not during peak fever.

- Urbanization, travel, and poor mosquito control drive dengue resurgence.

Dengue fever has haunted human populations for centuries, but today, it has evolved into a far more dangerous global threat, especially in Latin America.

In a landmark 1998 review published in Clinical Microbiology Reviews, Professor Duane Gubler traced how dengue re-emerged as urbanization, global travel, and mosquito expansion pushed the virus into new regions.

As outbreaks intensified, multiple dengue serotypes began circulating simultaneously within the same communities, a shift that fundamentally changed dengue’s clinical impact.

That change mattered. It coincided with the rise of dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF), a condition now largely encompassed under the World Health Organization’s classification of severe dengue.

In this blog, we break down the key insights from Dr. Gubler’s review to explain how and why dengue fever differs from dengue hemorrhagic fever, and what those differences mean for diagnosis, monitoring, and survival in the modern dengue era.

Table of Contents

Dengue fever: the “classic” illness

Headache. Photo by Jose Navarro via Wikimedia Commons.

In Gubler’s review, classic dengue fever is described as most common among older children and adults, with abrupt fever and a cluster of symptoms that can include headache, pain behind the eyes, body aches, nausea/vomiting, weakness, and rash.

Fever often lasts several days, and some people experience a “saddleback” pattern where fever improves briefly then returns.

Laboratory findings can include low white blood cell counts and low platelets, and liver enzymes can rise, sometimes substantially, during certain outbreaks.

Importantly, dengue fever can include mild bleeding (like nosebleeds or gum bleeding). This fact often confuses people: they assume any bleeding equals “hemorrhagic fever.”

But the review’s takeaway is that uncomplicated dengue fever is usually self-limiting and rarely fatal, although recovery can be prolonged with weeks of fatigue (especially in adults).

The danger is not that dengue fever is always severe, it’s that you can’t reliably predict who will worsen without monitoring for warning signs during the critical phase.

Dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF)

Human red blood cells. Photo by Arek Socha via Wikimedia Commons.

DHF, as described in the review, is primarily a disease of children under 15 years old in many endemic settings (though adults can also be affected).

Early illness can look similar to dengue fever, which is why DHF is hard to diagnose in the first febrile days.

The major shift happens around defervescence, when the fever starts to go down, because that is when the most characteristic and dangerous process emerges: plasma leakage due to increased vascular permeability.

Clinically, DHF is defined by a combination of thrombocytopenia (low platelets) and hemoconcentration (a sign of plasma leakage).

In addition, bleeding manifestations symptoms can range from skin petechiae (non-blanching spots) to more serious gastrointestinal bleeding.

The review emphasizes that many deaths are driven by shock from plasma leakage, not “bleeding alone”.

This is why DHF is best understood as an emergency of circulation and permeability, blood volume is effectively “lost” into tissues even without major external bleeding.

To note is that many guidelines today use the term “severe dengue” rather than DHF/DSS, but the key concepts overlap, especially plasma leakage leading to shock, severe bleeding, and severe organ involvement.

The core difference

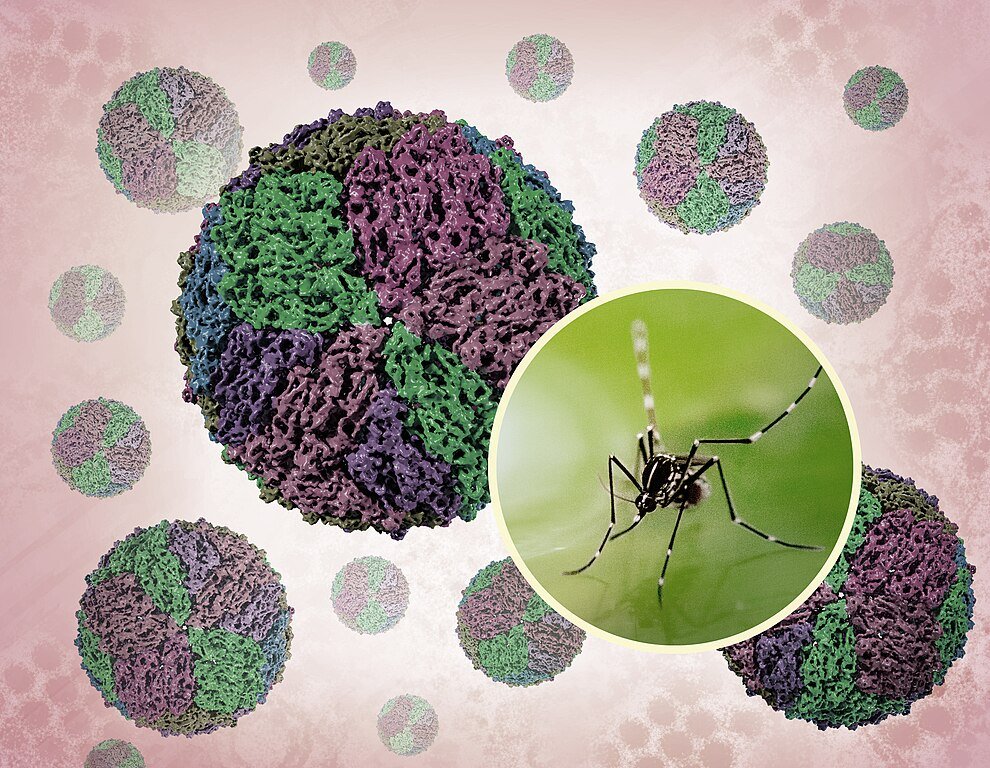

Dengue virus particles illustrated using cryoelectron microscopy and Aedes aegypti mosquito. Photo by NIAID via Wikimedia Commons.

If dengue fever is the body’s systemic response to infection (e.g., fever, aches, rash, and sometimes mild bleeding) then dengue hemorrhagic fever is a capillary leak syndrome where vascular permeability changes threaten circulation.

The review’s clinical framing makes this distinction clear: plasma leakage and hemoconcentration are central to severe disease, and the timing around defervescence is a critical danger window.

This matters for real-life decision-making. A person can look “better” because the fever is dropping, while quietly entering the most dangerous phase of illness.

That is why modern public health guidance highlights warning signs (abdominal pain, persistent vomiting, mucosal bleeding, lethargy/restlessness, and fluid accumulation) and stresses rapid medical evaluation when these appear, especially around the time fever resolves.

Why severe dengue happens

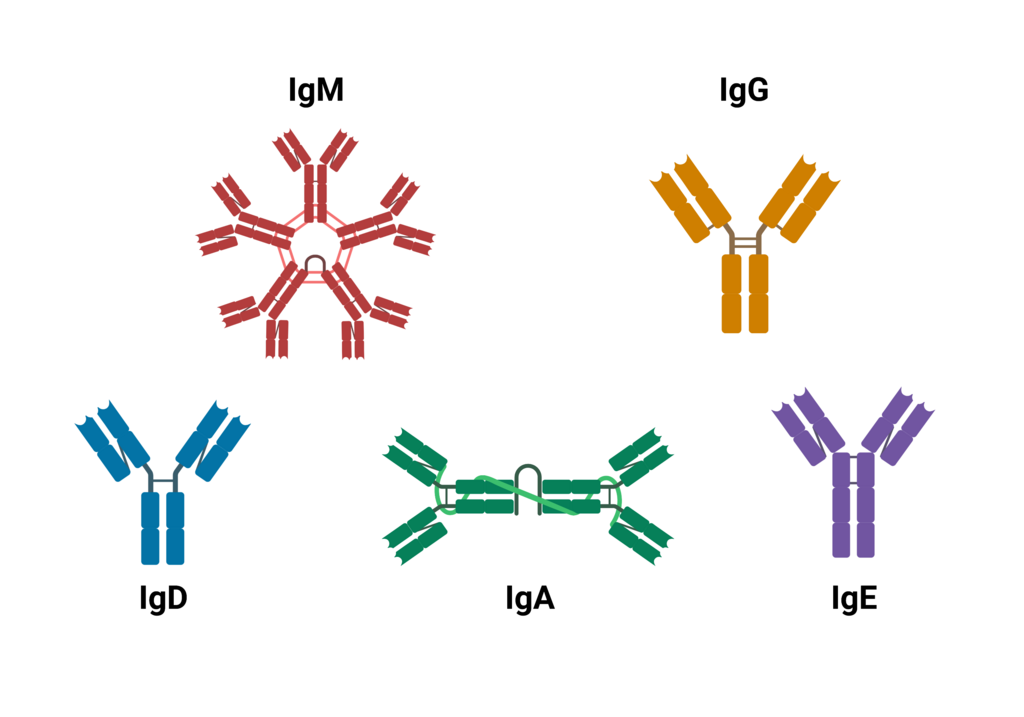

Antibody isotypes. Photo by עברית via Wikimedia Commons.

Gubler’s review explains that the pathogenesis of DHF/DSS has been controversial, but two major (not mutually exclusive) ideas dominate.

First is the secondary infection / immune enhancement hypothesis, often discussed as antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE).

ADE develops during a second infection with a different serotype, pre-existing antibodies may bind virus without neutralizing it, potentially increasing infection of immune cells.

This amplifies inflammatory mediator release that contributes to vascular permeability.

Second is the role of viral factors, including genetic variation among dengue strains that may influence epidemic potential and disease severity.

The review notes that dengue viruses vary in nature and that outbreaks can differ dramatically in clinical severity even within the same serotype, suggesting strain-level effects.

Bottom line: severe dengue is likely the result of both host immune context and viral characteristics, interacting with age, genetics, and other risk factors.

In conclusion

Dengue in Latin America is not a single, predictable illness. As Dr. Gubler’s review shows, the real danger is not how sick someone looks on the first day, but how the infection evolves inside the body over time.

For many patients, classic dengue fever resolves on its own. But severe dengue is a different disease process altogether. It is driven by plasma leakage, hemoconcentration, and shock, not bleeding alone.

The most dangerous window often arrives when the fever breaks. At this stage, patients may seem to be improving, even returning home, while fluid silently escapes from blood vessels. Circulation falters, organs are deprived of oxygen, and risk rises fast if warning signs are missed.

In severe dengue, bleeding is not the defining threat. Loss of effective blood volume is. Recognizing this difference, early and clearly, can be lifesaving in clinics and hospitals across the region.

As rapid urban growth, crowded housing, cross-border travel, and uneven mosquito control continue to fuel dengue transmission in Latin America, these clinical lessons matter more than ever.

Dengue’s resurgence is not just about mosquitoes or viruses. It is about timing, close monitoring, and informed care, factors that ultimately decide who recovers and who does not.

Stay informed

Photo by Zuko.io Images via Wikimedia Commons.

If you live in or travel to dengue-endemic regions, do not ignore symptoms simply because fever is improving.

Know the warning signs. Seek medical care early, especially during the critical phase around defervescence.

For clinicians, educators, and public health advocates: keep emphasizing that severe dengue is a leak-and-shock emergency, not just a bleeding disorder. Clear communication saves lives.

At Pathogenos, we break down complex infectious disease science into practical, actionable insight.

Follow, share, and stay informed, because understanding pathogens is the first step toward stopping their impact.