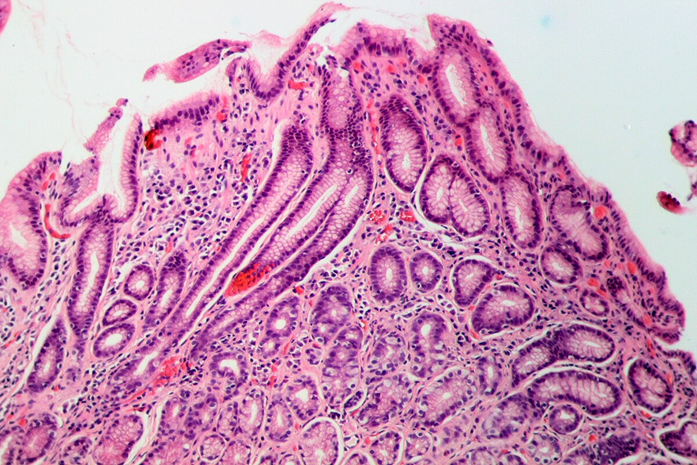

Source: Amin via Wikimedia Commons.

Highlights

- Metronidazole use persists despite widespread pylori resistance.

- Drug efficacy depends on intracellular reductive activation.

- pylori activates metronidazole inefficiently.

- Resistance drives eradication failure and persistent infection.

Metronidazole is a widely used antimicrobial agent for the treatment of anaerobic, protozoal, and microaerophilic bacterial infections.

Importantly, it is a first-line antibiotic prescribed to combat Helicobacter Pylori ( H. pylori) infection in Latin America.

The problem is that H. pylori resistant to metronidazole is undermining its efficacy in treating H. pylori infection. This is an urgent problem as recent studies indicate the same key finding:

H. pylori strains isolated from patients in Latin America are mostly resistant to metronidazole compared to other antibiotics, such as levofloxacin.

But to understand this high resistance, we first need to understand the mechanism of action of metronidazole.

So how does it work? In this blog, we explore metronidazole’s mechanism of action.

Reported Mechanism of action of metrodinazole

Source: PickPik

Metronidazole is a synthetic nitroimidazole antibiotic kills susceptible microorganisms such as H. pylori by causing lethal DNA damage.

How it works is that it diffuses into bacterial and protozoal cells and undergoes intracellular reduction.

This activation allows metronidazole to bind directly to DNA, disrupt the helical structure, and induce strand breaks that lead to cell death.

To note is that although metronidazole can enter both aerobic and anaerobic organisms, it works mainly in anaerobic and microaerophilic pathogens where these reduction reactions occur.

In brief, metronidazole acts through a four-step process:

- First, it passively crosses the cell membrane of anaerobic ( without oxygen) microbes

- Second, intracellular enzymes reduce the drug and generate reactive free radicals. This reduction drives further drug uptake and amplifies toxicity.

- Third, the reactive metabolites damage microbe DNA and destabilize the genome.

- Finally, the cell degrades the cytotoxic byproducts.

Mechanism of action of Metronidazole against H. pylori

Source: PublicDomainPictures via Wikimedia Commons.

Metronidazole also acts against facultative anaerobes such as H. pylori and Gardnerella vaginalis, though the exact mechanisms in these organisms remain unclear.

Metronidazole still requires intracellular reductive activation in H. pylori to generate reactive intermediates that damage DNA.

Once activated, those metabolites disrupt DNA structure and cause strand breaks, just as they do in other susceptible organisms.

That shared requirement for reduction is why metronidazole can work against H. pylori at all.

The key difference is efficiency and consistency of activation.

H. pylori is a facultative anaerobe (thrives in low-oxygen environments), not a strict anaerobe, and it reduces metronidazole less efficiently.

Small changes in bacterial redox enzymes (such as mutations affecting nitroreductase activity) can sharply reduce drug activation.

When activation drops, DNA damage no longer reaches lethal levels, and resistance emerges.

So the mechanism is the same in principle, but H. pylori sits at the edge of metronidazole’s effective range, making treatment success highly sensitive to bacterial genetics and local resistance patterns.

Why This Matters

Source: RDNE Stock project via pexels.

Metronidazole remains a first-line antibiotic for Helicobacter pylori across much of Latin America, yet resistance now undermines its core purpose: eradication.

When clinicians rely on a drug that no longer works, patients cycle through failed treatments, remain chronically infected, and face higher risks of peptic ulcer disease and gastric cancer.

High metronidazole resistance also distorts clinical decision-making—guidelines assume efficacy that no longer exists, empiric regimens fail, and health systems absorb the cost of repeated therapy.

In regions with high H. pylori prevalence like Latin America, this disconnect between pharmacology and reality directly translates into preventable disease and widening health inequities.

Understanding how metronidazole works clarifies why resistance is so damaging and why continued reliance on it is risky.

The drug depends on intracellular reduction to generate DNA-damaging radicals; when bacteria evade or blunt this activation, the antibiotic loses its lethal edge.

In H. pylori, where the exact molecular details remain incompletely defined, resistance signals deeper biological adaptation rather than poor adherence or misuse alone.

Explaining the mechanism, indications, and limits of metronidazole reframes treatment failure as a predictable outcome of microbial evolution.

That clarity matters. It supports evidence-based guideline updates, prioritizes resistance surveillance, and pushes clinicians toward alternative regimens that actually reflect the biology of H. pylori in high-burden regions.

Take Action

Clinicians and researchers should recognize that rising metronidazole resistance limits its reliability for H. pylori eradication and consider evidence-based alternatives informed by local resistance patterns and emerging research.

Staying current on the biology behind treatment failure supports better therapeutic decisions and patient outcomes.

Subscribe to Pathogenos for clear, research-driven updates on antibiotic resistance, infectious disease mechanisms, and clinically relevant insights grounded in the scientific literature.